Published September 25, 2025

When a virus sweeps through a city, the first warning sign is often in the sewer. At Michigan State University’s Water Quality and Environmental Microbiology Lab, also known as the Rose Lab—named for Homer Nowlin Chair and Director of the MSU Water Alliance, Joan Rose—scientists track what’s moving through our communities by monitoring wastewater.

Wastewater is the water that leaves our homes and businesses after flushing the toilet, washing the dishes, taking a shower, or doing a load of laundry. By testing this water, the Rose Lab can detect early signs of viruses and bacteria that affect human health.

“We’re looking for gene copies of DNA and RNA specific to pathogens,” explained Assistant Research Professor, Nishita D’Souza. “That data helps track changes in disease levels.” In other words, if wastewater tests show more viral markers this week than last week, it’s a warning that cases in the community are increasing.

Data is then shared with health departments and the public through state dashboards and the National Wastewater Surveillance System, which use it to help track community health trends.

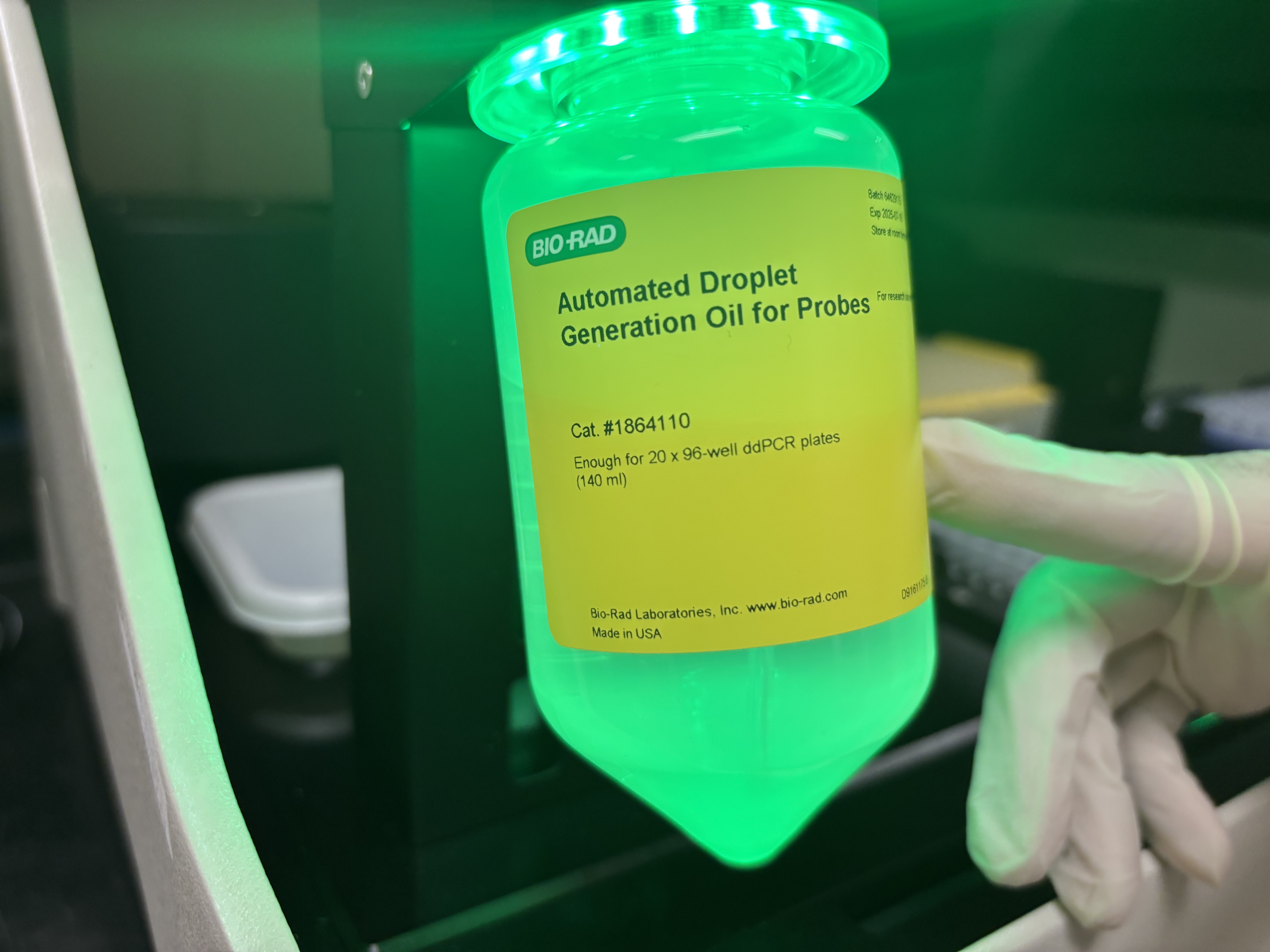

Automated droplet generation oil helps the Rose Lab run droplet digital PCR, creating thousands of tiny reaction chambers to detect viruses in wastewater.

What they test for

The Rose Lab monitors wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), influenza, RSV, Candida auris, and norovirus. Once samples arrive from various sites in Michigan, including Lansing, Manistee, and Delhi Township, they are concentrated, extracted, then tested using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR).

ddPCR measures the concentration of the target of interest (viral or fungal) and is sensitive to very low levels found in wastewater.

D’Souza explained that the lab also runs a multiplex respiratory assay, or a single test that can screen for several viruses at once. This kind of combined testing is faster and most cost efficient than running separate tests for each virus and helps show how illnesses can overlap during peak respiratory season.

A freezer in the Rose Lab holds wastewater samples preserved for genetic testing and long-term pathogen tracking.

Tracking influenza

Among the viruses the Rose Lab monitors, influenza remains one of the hardest to track in wastewater. Postdoctoral Research Associate and former lab member Anwar Kalalah explained that influenza primarily infects the respiratory system, so only small amounts of viral RNA make their way into stool. That means wastewater concentrations are much lower than for viruses that replicate in the gut, like norovirus or SARS-CoV-2.

These low levels pose challenges for monitoring. Yet advanced PCR and digital PCR tests are able to pick up enough genetic material to confirm the virus is present in many cases.

To improve understanding of how the virus changes, Kalalah has turned to genomic sequencing. Short-read sequencing divides genetic material into small fragments, improving the odds of capturing usable segments. Long-read sequencing works with larger segments, revealing more about the virus’s structure and evolution.

While challenging because of the low levels of virus, sequencing has opened new possibilities for tracking influenza in wastewater, but progress has been slow. “We haven’t sequenced enough of the H5 genome yet to make meaningful conclusions,” Kalalah said, referring to the avian influenza subtype. He explained that the next step will be to use enrichment methods that increase the amount of influenza material in a sample, making it easier to detect even trace amounts in the future.

Beyond the lab

The Rose Lab’s work is part of a much bigger shift in public health. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, wastewater surveillance has expanded across the United States. In 2022, the CDC reported that more than 1,200 sites were contributing data to the National Wastewater Surveillance System. Today, the agency reports that its network typically includes more than 1,300 sites, covering nearly 150 million people. But even as the national network expands, recent funding cuts have forced some state and local programs to pause their work, raising concerns about blind spots in virus tracking.

Globally, countries including Finland have adopted wastewater monitoring to track pathogens without relying solely on clinical testing, and Australia is in the process of launching a national program.

This expansion underscores the significance of what happens in East Lansing. The same methods used at MSU to monitor COVID-19, RSV, norovirus, C. auris and influenza are being adopted as a permanent part of disease monitoring infrastructure. Researchers argue that wastewater could one day serve as an all-purpose warning system not only for seasonal viruses, but also for antibiotic resistance and future pathogens we’ve yet to face.

Story by Aja Witt